On Silicon Valley Bank, And Finance As A Public Good

The Fed essentially nationalized a lot of the banking business on Sunday night.

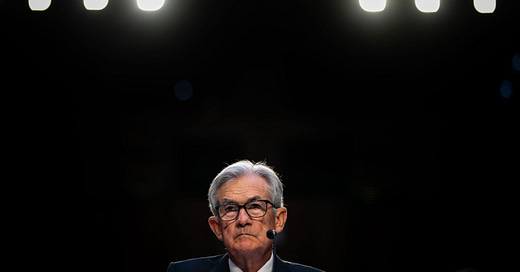

My latest piece is up at Vanity Fair on the Silicon Valley Bank debacle. As usual, I won't summarize the whole thing here, but will instead use this post to develop one of the points I make in the piece a bit further, and to explore another important issue — namely, that Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell effectively nationalized a significant chunk of the American banking business on Sunday night.

Let's begin with SVB. There are three separate failures in the SVB debacle. A macroeconomic failure from the Fed, a regulatory failure from Congress and a management failure from SVB executives. None of these are mutually exclusive -- if anything, the opposite is true. A bad policy landscape made it easier for bad managers to screw up, but those policy errors do not excuse the bank's judgment. "You didn't stop me when I decided to flush all of this money down the toilet!" is never a very productive thing to say, and nobody would be saying it now if a certain ideologically motivated set weren't desperately trying to exonerate every last rich guy involved in this mess.

The SVB crash is mechanically similar to a lot of bank failures. The bank used short-term debt (deposits) to fund long-term bets that didn't pay out. These longer-term investments were relatively safe in terms of default risk -- Treasurys and government-backed mortgage bonds from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Borrowing short and lending long is basically how all banking works, but the size of the bet was very large -- roughly half of the bank's total assets -- and exposed the bank to significant interest-rate risk, which SVB decided not to hedge. When the Fed raised interest rates, the market value of the bank's bond portfolio was crushed, so when depositors started withdrawing their money, the bank had to sell its bonds at a loss, and eventually people panicked and the bank failed.

That is bad bank management, and the details of SVB's operations may prove to be worse. We don't know, for instance, why more than 95 percent of SVB's deposits were uninsured, or why serious businesses were keeping up to half a billion dollars in bank accounts earning nothing or next-to-nothing, or why so many very rich VC people were parking huge personal balances at SVB. It could very well be an innocent confluence of events, but it would be best for the Department of Justice to make sure.

For the moment, however, the worst aspect of this debacle is the regulatory failure from Congress, because it was the single easiest variable to control, with the most obvious foreseeable consequences. Back in 2018, Congress decided to relax regulations on 25 of the 38 largest banks in the country -- specifically, the 25 smallest of the 38 largest banks in the country -- but still some very big players. Supporters of the deregulation program claimed that the tighter rules for large banks adopted after the 2008 crash were unfair to banks with $50 billion to $250 billion in assets -- these banks weren't really too big to fail like the multi-trillion-dollar Wells Fargos and JPMorgans of the world. They weren't going to get bailed out in a crisis, and they shouldn't be forced to abide by the same tighter risk protocols.

When Congress talked about this stuff, they made it sound like the banks were being drowned in oceans of paperwork with obscure definitions, and just didn't have time to issue loans while they dealt with all these pesky forms. But of course everything at issue was straightforward -- how much debt banks could use to finance their operations, and how much cash they had to keep in reserve. Banks would have to calculate this stuff regardless, the only question was where the ratios would be set.

Certainty is hard to come by in economics, but we can now say without a doubt that it was flatly incorrect to claim that these banks posed no systemic risk and therefore did not need to be regulated as if they did. We know this because regulators from the Federal Reserve, Treasury and the FDIC officially declared Silicon Valley Bank "systemically important" on Sunday night so they could save all of its depositors from losses.

I spent a lot of time reporting on this law at the time, and found the experience surreally toxic. Nobody ever just came out and said it, but the basic attitude from the bill's Democratic supporters seemed to be that it was unfair to harp on Democrats doing something corrupt and stupid when Republicans were corrupt and stupid as a matter of principle. The political calculation seemed obvious enough. Democrats in tough re-election races would do these banks a favor, the banks would give them a lot of campaign cash, which they would spend trying to survive the midterm. And when you looked at the fundraising numbers, lo and behold -- these Democrats were getting a ton of money from banks.

Seventeen Democrats ultimately voted for that bill, and without Democratic support, it would not have cleared a filibuster and would not have made it to Trump's desk. I focused on Democrats in my coverage because they had the power to stop one of Trump's top legislative priorities, and instead decided to help him deregulate banks that controlled hundreds of billions of dollars in assets. For this, I caught more flak from Senate staffers than anything I ever wrote about in the decade I worked at HuffPost.

Here's the big feature we ran on the bill. And here's Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), one of the 17 Democrats who voted to deregulate SVB, trying to deflect blame in an interview with NBC News:

"I think it’s early. We need to complete the investigation of what actually happened at Silicon Valley Bank. All the regulation in the world isn't going to fix bad management practices, and it appears that that’s one of the problems at SVB," Shaheen said. "But depending upon the outcome, I think it’s appropriate for us to take a look at what we did and see if it still holds."

Early was 2018. By the time regulators are invoking emergency powers and implementing economy-wide rescue operations, it is late, perhaps too late. And of course regulation can fix bad management practices, that's what regulation does. Imagine Shaheen saying something like this about, for instance, gun laws.

So much for the history here. The really wild aspect of this crisis is the future. The key event in SVB's failure was the collapse of its bond portfolio. The central bank noticed this, and is now trying to fend off other potential SVBs by essentially exempting bonds owned by banks from the consequences of the Fed's recent monetary policy operations.

Under its new emergency facility, the Fed will stand ready to lend money to banks, so long as they can post bonds as collateral. That much is garden-variety lender-of-last resort central banking. The really shocking change is how much the Fed will allow banks to borrow against this collateral. Instead of tying the loan to some price attached to the bond's value on the open market -- which has collapsed -- the Fed will allow banks to borrow the full amount they initially paid for the bond. In short, if your bank bought a lot of bonds that have declined in value and need to raise money, the Fed will pretend the bonds haven't lost any money.

This is not just a great deal for the banks -- it's a major change in the Fed's economic role. The Fed is basically saying that the market for a huge class of assets -- Treasurys and Fannie- and Freddie-backed mortgage bonds -- doesn't really matter, so long as you're a bank.

Taken together with the move to rescue all depositors at both SVB and Signature Bank, Jerome Powell effectively nationalized a significant portion of the banking business on Sunday. It is extremely difficult to undo the expectations created by this type of rescue. Everybody now knows that all deposits at American banks will be protected by the Fed, as will the value of a large class of bonds at American banks.

All of this is, I think, good policy given where things are after a massive regulatory failure. The $250,000 deposit insurance limit is arbitrary, and protecting depositors during financial turmoil has long been established as an essential financial crisis-fighting measure, perhaps the essential financial crisis-fighting measure. But in this particular crisis, nobody — including, apparently, the Fed — knows exactly how widespread the banking system’s bond problems are. Unlimited deposit insurance will help prevent one bank failure from cascading into several, while the bond guarantees will help limit the number of bank failure nodes.

The corollary to all this public support, of course, is that it makes very little sense to pay bankers large salaries and allow banks to book very large profits for the privilege of managing government-protected deposits and government-protected bond portfolios. Some kind of structural reform is in order. For those emotionally attached to existing financial infrastructure, banks could be regulated more tightly and face new fees associated with this work -- higher deposit insurance premiums, new bond insurance premiums, etc. Alternatively, these operations could just move over to the Fed itself, or another public entity regulated by the Fed, allowing banks to focus on the thing banks are most famous for, making loans.

In the meantime, the Fed's monetary policy program is in trouble. The central bank has been raising interest rates over the past year because it believes tighter financial conditions will lead to a weaker labor market, lower wages, and eventually lower prices. But it is clear from the rescue that the Fed has not been monitoring the effect of all this financial tightening on the financial system. We don’t even know which rate hikes are fully priced into bond values. Do today’s financial conditions reflect interest rate increases from March? July? December? You cannot manage an economy through bank failures — the damage is too great, and you may not be able to extinguish the fire. But preventing bank failures by loosening financial conditions will, of course, stymie the Fed’s efforts to fight inflation by tightening financial conditions. You can’d really do both at the same time.

For quite a while now, I’ve been protesting the use of interest rate increases as a cure for inflation. But in the current moment, I can’t see how the Fed can maintain financial stability without either taking a break from its attack on inflation, or figuring out a new way to fight it — price controls, credit controls, commodity supply management, even tariffs and trade, so long as it’s something other than interest rate hikes. The crisis may only be beginning.

“Everybody now knows that all deposits at American banks will be protected by the Fed, as will the value of a large class of bonds at American banks.”

Not at the 4000 community banks.

Thanks for your insight, it’s appreciated. As upset as I am that bankers cannot seem to avoid bail outs again and again by government, including loans on bad bets already made, I’m a bit more concerned the fed seems to arbitrarily have closed signature for offering services to crypto companies, which haven’t been made illegal. I get the moral hazard of gambling, but casinos are allowed banking services and I fail to grasp the difference. I hope it’s not just sufficient donations to the politicians and regulators, but it feels that way...