Straight-Up McCarthyism

Trump appointee Christine Wilson is smearing antitrust reformers as agents of 'tumult and destruction.' It's disgraceful.

Earlier this month, FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson issued a malignant screed smearing antitrust reform advocates as brutal Marxists who “despise the rule of law.” She throws around a lot of fancy names — John Stuart Mill, Friedrich Hayek and Karl Marx, among others — to essentially accuse FTC Chair Lina Khan of pursuing the violent elimination of property rights and the state itself. Wilson was probably careful enough with her language to avoid a libel suit, but it’s not a subtle speech. Under a section headed “Destruction and Revolution” she muses that — perhaps! — Khan “believes that tumult and destruction will lead inevitably to progress” so that “near-term harms can be dismissed as the price of progress.”

It’s obvious that Wilson is not an intellectual historian. She’s doing her best Mark Levin impression, calling a bunch of stuff she doesn’t like “Marxist” and gesturing vaguely to mass butchery that has nothing to do with Lina Khan, the FTC or antitrust reform. People who “despise the rule of law,” do not build reform programs on a detailed reading of antitrust statutes and judicial verdicts — they just break the law when it gets in their way. During the antitrust debates on the left over the last few years, Khan and her cohort have routinely earned the ire of actual, existing Marxist scholars (none of whom, to be clear, have advocated mass slaughter). Marxists generally view the legal frameworks of Khan, Tim Wu, Barry Lynn, Zephyr Teachout, Matthew Stoller and their allies as excessively narrow and legalistic. Khan et al like competition policy as a reform tool precisely because it leaves so many complex decisions about economic production and distribution to markets. The basic idea is that if lawmakers fix the distortions created by excessive corporate concentration, the market will generally work just fine (or at least, much better).

I don’t always agree with the new crop of antitrust reformers, but it’s simply impossible to take seriously the idea that any of them pursue social upheaval for political gain. Wilson should apologize, resign, and go back to making gobs of money defending giant corporations. It would serve the public interest to have her arguing the wrong side of a major antitrust case.

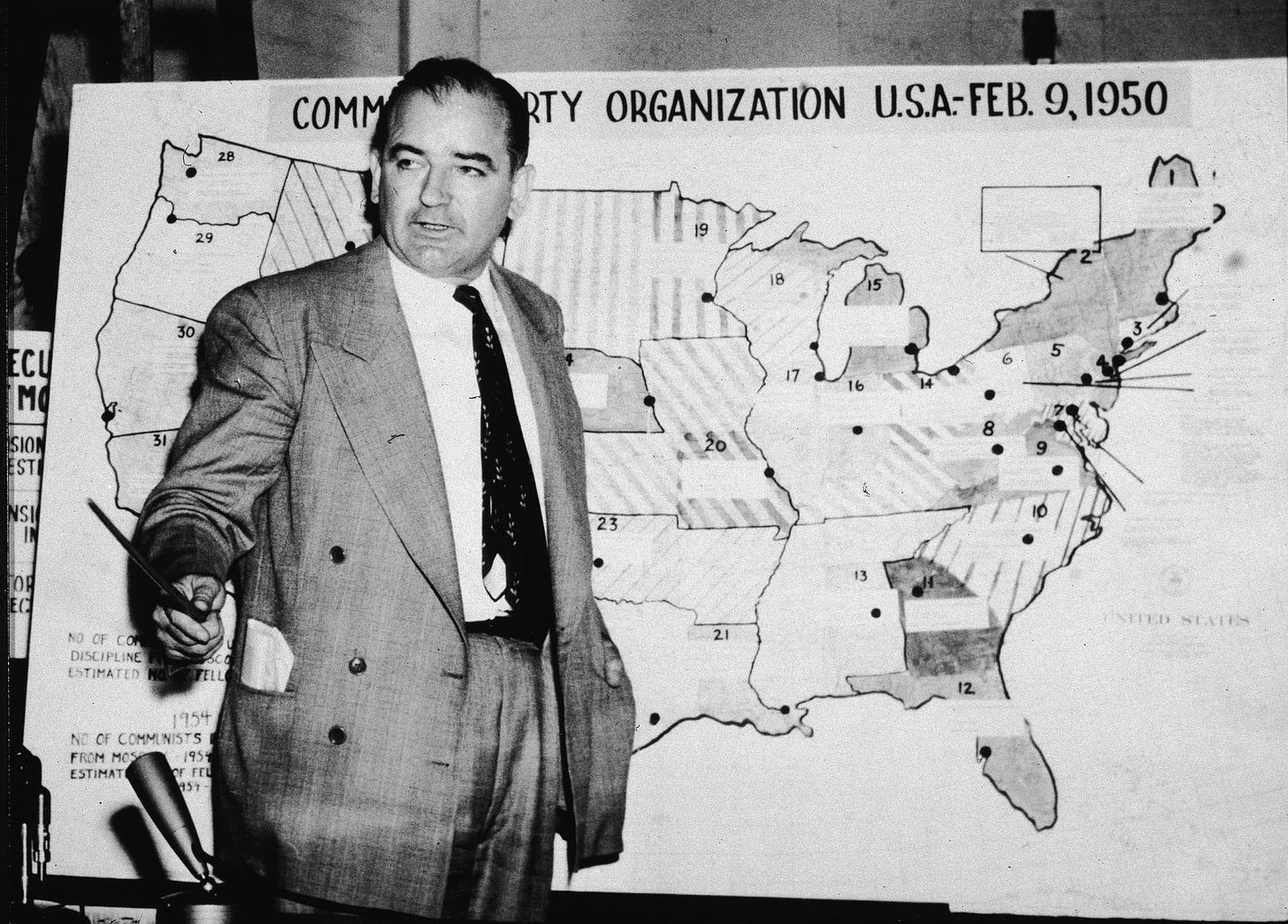

For now, however, we can observe that Wilson, a seated government official, is engaging in straightforward McCarthyism. Her speech reveals that despite all the recent talk of a “populist” conservative awakening, the Republican Party still routinely aligns itself with big business at the level of federal policy. Wilson is a former Delta Airlines attorney who Trump appointed to the FTC in 2018, about the same time that he was lifting regulations on banks with hundreds of billions of dollars in assets. As of this moment, conservatism remains the favored refuge of monopoly.

But this is a history newsletter. Or at least, those of you who write me are always asking for more history. So in honor of Wilson’s McCarthy impression, here’s an anecdote from The Price of Peace about a bunch of Keynesian economists getting cancelled because conservatives thought they were going to destroy freedom, God and America. See the book for citations.

In 1948, Howard Bowen, dean of the University of Illinois College of Commerce and Business Administration, asked John Kenneth Galbraith if he would be interested in chairing the burgeoning economics department at his school. Galbraith was intrigued. He had taught at both Harvard and Princeton when between Roosevelt administration jobs, but he’d never landed a tenured position, much less a job heading an entire department. At age forty, he was still considered a young man in academia, and although UI didn’t carry Ivy League prestige, Galbraith often found the aristocratic culture on elite campuses stifling. He agreed to fly out to Champaign-Urbana for an interview, carefully warning Bowen that his family wasn’t quite sold on the idea of settling down in a small midwestern town: “It is conceivable that my wife believes the United States ends at the Alleghenies.”

Bowen liked New Dealers, and he liked Galbraith. He had served in FDR’s Commerce Department during the war and performed a stint on Capitol Hill as the chief economist for the Joint Congressional Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation. Like Galbraith, Bowen was a top beneficiary of the new hierarchy of Washington expertise established by the Roosevelt administration. When FDR brought Keynesian economists to the nation’s capital to replace the Wall Street grandees who had dominated economic policy making in the 1920s, an entire generation of inexperienced young men were transformed into professionals armed with impressive government credentials. Now Bowen was bringing many of them back into the academic fold. The twenty appointments he had overseen at the economics department in his short tenure at Illinois included a host of Keynesians who were quickly building reputations for themselves as important scholars, most prominent among them Franco Modigliani, a future Nobel laureate.

For Keynesian economists, the late 1940s and 1950s weren’t just an opportunity to flex their credentials; the era seemed to vindicate their entire school of thought, as the federal government deployed the ideas of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money to manage the booms and busts of the business cycle. World War I had ended with a sharp, devastating recession, but Keynesian policy maneuvering after World War II ensured that the war boom never really ended. Soldiers who returned home from Europe and the Pacific with money in their pockets spent it on everything from new cars to new houses and all of the ingenious home appliances that had been banned during the war to make way for military production. Corporate profits surged and tax rates went down. Unemployment generally fluctuated between 2.5 and 6 percent, as first Truman and then Dwight D. Eisenhower began using Keynesian demand management to heal or head off economic downturns. It was a massive and permanent change in the scale and responsibility of the American government. During the Eisenhower years, government spending averaged over 17.5 percent of the total U.S. economy—far more than even FDR’s peacetime budgets, which had peaked at 11.7 percent on the eve of World War II. From 1947 to 1974, the annual unemployment rate peaked at 6.8 percent, while the monthly rate never eclipsed 8 percent—figures that those old enough to remember the Depression would have celebrated as astounding prosperity.

The postwar boom also radically transformed American higher education. The 1944 GI Bill had changed the meaning of a college degree by providing unprecedented federal tuition support for World War II veterans. More than 7.8 million Americans eventually took advantage of the GI Bill’s higher education benefits. University classrooms that had once been small outposts of intergenerational family privilege were flooded with a wave of students seeking a foothold in the burgeoning American middle class. After decades of depression, state government budgets were suddenly flush, as the booming postwar economy raised incomes and returning soldiers bought houses and paid property taxes. There had never been so many students to teach or so much money to pay professors.

Keynes and FDR were gone, but it seemed their disciples were about to inherit a new era of personal influence and national prosperity. But when Galbraith arrived at Illinois, he instead found himself in the middle of a statewide political firestorm.

The controversy centered around Ralph Blodgett, an archconservative who had been warning his fellow economists since at least 1946 that “innocent-sounding things” such as “full employment,” “a system of social security,” and “higher minimum wages” would lead to the “destruction” of the U.S. economic system. Bowen had little patience for Blodgett’s ideas and was steadily demoting him. He stripped him of some undergraduate teaching duties and added insult to injury by replacing a Blodgett-authored textbook in the introductory curriculum with the new textbook by Paul Samuelson. When the University of Florida offered Blodgett a $500 raise to move south, Bowen decided to let him go.

What followed was chaos, according to the economic historians Winton Solberg and Robert Tomlinson. Conservative faculty went to the press, and the Champaign-Urbana News Gazette started bashing Bowen as a man planning a “heavy infiltration” of “leftist and ultra liberal” New Dealers opposed to “good American principles,” while a university economist gave a speech accusing Bowen of trying to “pack” the faculty with radicals. An internal university committee cleared Bowen of subversive intent, but not before newspapers in Chicago and the Twin Cities started picking up on the story. University president George D. Stoddard was shocked by a Chicago Daily News headline blaring “Stoddard Denies Reds in Control,” and both the Champaign-Urbana Courier and The News-Gazette started calling for Bowen’s head. Before leaving town, an embittered Blodgett gave a farewell address declaring that although there were no “reds” currently on staff in the economics department, there were “a few pale pinkos . . . and great reds from little pinkos grow.”

Blodgett settled in at Florida, which he found ideologically hospitable and, much to his relief, “without the chosen people”—Jews— whom Bowen had been bringing on at Illinois. But even with Blodgett comfortably out of the picture, the controversy continued to escalate. The Illinois Republican Party made it a top political priority to secure positions for hardline conservatives on the university board of trustees. State representative Reed Cutler decided that Blodgett had been too charitable in his assessment of the faculty: “They’ve got some professors over there that are so pink you can’t tell them from reds.” Another state legislator, Ora D. Dillavou, went further, declaring that there were about fifty “Reds, pinks and socialists” on staff. When the university president asked him for names, Dillavou responded that the “University is being used to indoctrinate youth with radical political philosophies. . . . the taxpayers of Illinois do not care to finance the cutting of our own throats.”

The school soon decided that Bowen had to go. Right or wrong, the situation had become too heated. His position as dean of the business school was allowed to lapse, though he was permitted to continue teaching while he looked for another post. He would go on to serve as president of Grinnell College and then as president of the University of Iowa. Illinois tried to make amends in 1975 by awarding him an honorary doctorate.

But the economics department was decimated. Sixteen professors resigned rather than subject themselves to further harassment. The university, wrote the outraged Modigliani, was “in the grip of a clique of faculty members interested not in scholarship but in personal power, not in the welfare of the University but in the gratification of their vindictive impulses.” Yes, the university had at last ended the “strife” in its economics department. “But let us be clear about it, it is the peace of death.”

Galbraith did not get the job.