Lessons From Keynes For The Crisis In Ukraine

Reimagining Liberalism for an Age of Total War

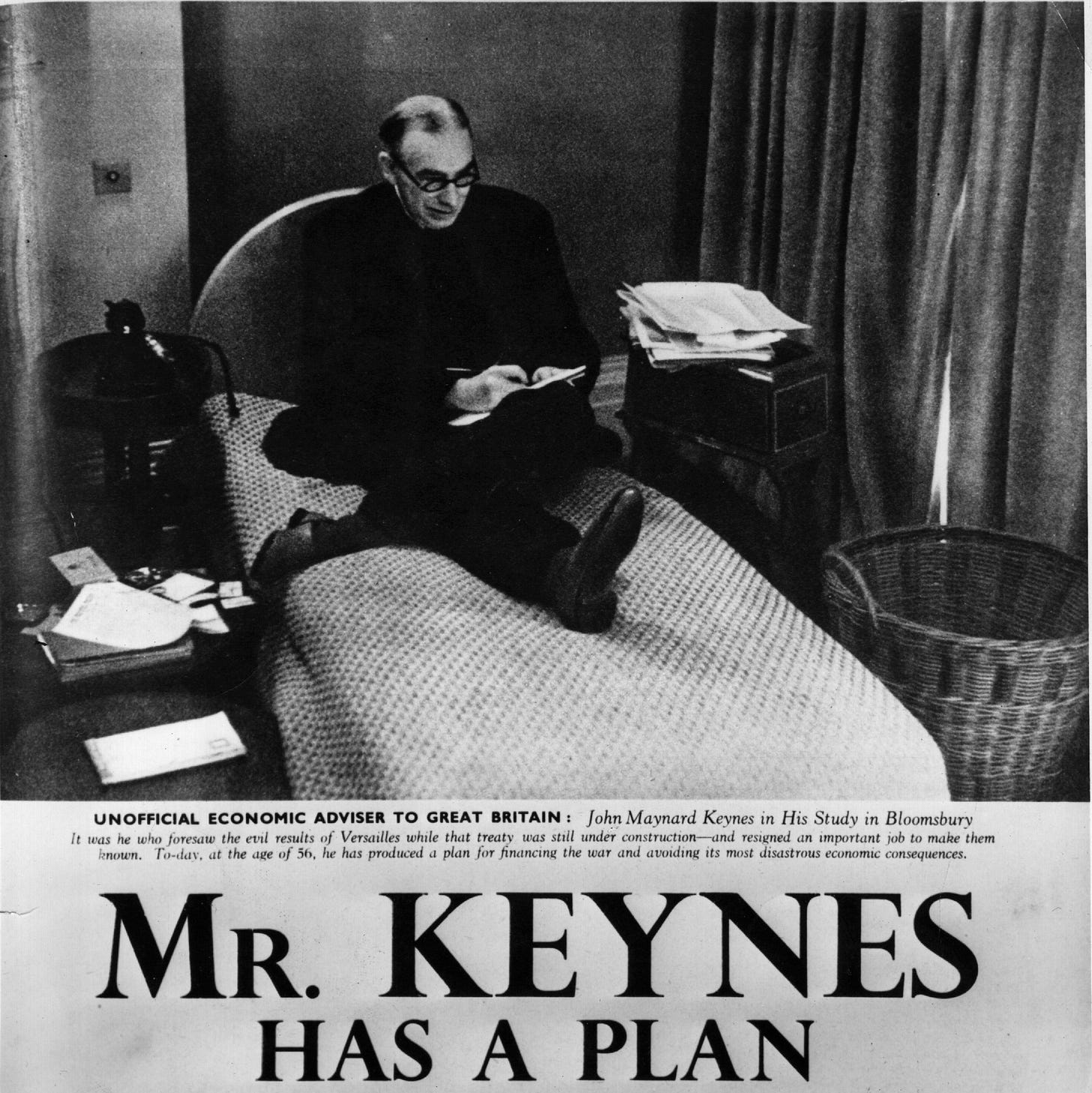

I gave a talk at an IMF event on Tuesday alongside Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Francesco Saraceno. On the off-chance that some of the subscribers to this newsletter were unable to make the event, I’m posting my prepared remarks here. The IMF folks had asked for some historical insights from Keynes regarding policy options in a post-COVID world, but events intervened and I gave them an essay on war and capital-L Liberalism. To the paid subscribers who have been clamoring for more history in their inboxes: let this tide you over, more will be ready soon.

Hello everyone and thanks so much for joining us today. I want to especially thank Nicoletta, Doug, Francesco and everyone at the Fund for taking the time and effort to make this event possible, but also thanks to everyone in the audience. At this point in the pandemic I think we have all had our fill of bad news and are being pretty choosey about which zoom events we attend, so I really appreciate all of you choosing this one. I need to say at the outset here that though I am currently a writer in residence with the Omidyar Network and a consultant for the Hewlett Foundation, my words here represent my own views and not necessarily those of the people who sign my paychecks.

One of the more interesting predicaments of becoming a Keynes scholar is that people are always asking you what John Maynard Keynes would have done about this or that crisis. And it's a funny question for many reasons, not the least of which is that often the people asking the question already know the answer. Keynes is very famous for advocating deficit spending during the Great Depression, and most casual intellectuals who can recognize his name know this is why he is famous. But for some reason many of them really enjoy hearing a bona fide Keynes expert say that, yes, Keynes would advocate deficit spending in response to whatever it is. I don't know why people like to do this, but they do.

It's also a funny question because for most of his life, Keynes didn't think about government deficits all that much. When Keynes married Russian ballet starlet Lydia Lopokova, the wedding was covered by newspapers on multiple continents and even earned a spread in Vogue magazine. But they were married in 1925 and the General Theory would not be released until nearly a dozen years later. My point here is not just that Keynes was very famous -- though of course he was -- but rather that he was an extremely flexible intellectual who was respected for advancing a wide variety of ideas over the course of his career. So the most precise answer to the question, "What would Keynes do?" is always something like, "Well, it depends on which Keynes you want to ask."

This is a roundabout way of praising Nicoletta for the topic and structure of this discussion. Because while the economic problems facing the world today are very serious, they are not the specific kind of economic problem that people so often associate with Keynes -- that of a straightforward shock to aggregate demand that must be met with government action. I think that describes the broad contours of the initial public response to COVID-19. Mask mandates and vaccine requirements did not shut down businesses around the world -- the pandemic did that. When my book came out in May of 2020, there were no formal lockdowns or government restrictions that prevented the book printers from operating, but people refused to work at the printing houses, and so my book promptly went out of print for six of the first seven weeks after its release. This was happening everywhere, and the initial impetus from governments to replace household incomes and maintain the flow of investment to productive activity was admirable. Indeed the focus on inflation today obscures the extent of recent material deprivation during the pandemic, even in rich countries like the United States. In January of 2021, 15 percent of American parents were reporting that their children did not have enough to eat -- about five times the typical rate. It is not an act of decadence or excess to attack such problems, it is basic democratic responsibility.

But of course that all feels like a long time ago now. Fortunately for Keynes scholars, demand shocks were not the only economic problems to which Keynes devoted his energies. I won't hide the political aspects of this story or my own ideological inclinations, but I want to emphasize that the reason we study great thinkers from the past -- or at least one of the better reasons we study them -- is to help us understand how they thought about the major problems of their day, not just to keep track of their solutions. From the point of view of 21st Century macroeconomics, Keynes often seems to anchor the Left edge of an ideological spectrum that ends on the Right with Friedrich Hayek. But Keynes was a capital L-Liberal in the fullest sense of the word. He meant the praise he showered on Hayek's Road to Serfdom every bit as sincerely as he did his criticisms of that incendiary book. So even folks in the audience today who loathe low interest rates and large government deficits may find some interest in the way Keynes thought about economic crisis in its many forms.

So let's enter the time machine and go back not to the Great Depression but to the two greatest disasters of Keynes' life -- the Great War that transformed the way he thought about international politics and the British Empire -- and World War II, a cataclysm that he both prophesied and spent the prime years of his life trying to prevent. In both conflicts, Keynes ran British war finance, where he spent a lot of time worrying about debt, inflation, and very large shipments of grain and iron.

Figuring out how to pay for and physically obtain everything Britain needed for World War I was an extremely daunting task and it was not one that could be easily left to markets to handle, for reasons that will immediately sound familiar. The world economy of 1914 was thoroughly globalized, in no small part because Britain -- by far the most powerful economic actor among the various empires scrambling for territory at the time -- was a tiny, semi-arctic island that had no choice but to import much of what it consumed. But once Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated the rules changed. It was all well and good to believe that free trade led to mutual prosperity, but warfare was not a mutual aid society. And the stuff that Britain typically imported was very, very important to the survival of ordinary British citizens -- a list of their top imports included cotton, wool, wheat, pork, cheese and timber. So without this stuff, British citizens literally could not clothe, house or feed themselves, nevermind equip an army.

Keynes had been raised as an ardent free trader and remained so for several more years after the war, but his view about the capacity of the state to manage the economy changed quite a bit. Britain didn't stop importing during the war -- it couldn't -- but it had to import from different places, and it had to coordinate its purchases with those of its allies in order to keep prices down. Had the Allied governments not been states fighting a war but private businesses seeking to limit their costs, most economists would probably describe their operations as that of a cartel. In 1915 Keynes was particularly incensed over an Italian wheat purchase from South America that drove up prices for a subsequent purchase Britain made. This caused all sorts of headaches because Britain was lending money to Italy, and it couldn't lend to Italy the money that it paid to Argentina.

In other words, top-down management of the economy was a mess. But it worked. For Britain. And the chief reason it did not work for Germany and Austria is that the British had an extremely powerful navy which they used to physically block imports to the Central Powers. Military historians dispute how severe the food shortages in Germany were, and there are plausible estimates putting the death toll from hunger anywhere from about zero to the hundreds of thousands. But whatever the official body count, by the end of the war both German imports and exports were down by roughly half, and that had a tremendous impact on the outcome of the war. This is an important point for the world today -- serious economic sanctions are often thought of as an alternative to violence. That is just not the case -- serious economic sanctions are a form of violence.

So although World War I revised Keynes' beliefs about the capacity for the state to manage production and distribution, the overall experience ultimately reinforced his more orthodox opinions about the global economy. Trade was good -- Britain did better than Germany during the war because it was able to do more trade, which made its war machine more efficient and its home front happier. So whatever the postwar world might look like, free trade between victor and vanquished would be essential to creating the prosperity necessary to rebuild Europe and maintain peace.

But the mere fact of the war made Keynes revise his views about the value of trade. Prior to the war, trade for Keynes was essentially an end in itself. Like millions of other educated Westerners, Keynes took for granted the idea that trade fostered mutual understanding and cultural appreciation, in addition to whatever efficiencies it brought from production. This combination of familiarity and prosperity was supposed to make the world more peaceful. When it didn't, Keynes and many others tried to come up with a system that could. The war forced Keynes to confront the idea that trade was a means to other political ends -- Britain did not reshape its political ambitions around its desire to trade with other countries, but was setting up its trading regime to accommodate its political choices. That's a key distinction.

There are a lot of economic critiques of the book that made Keynes an international celebrity -- The Economic Consequences of The Peace, first published at the end of 1918. But it is essential to recognize -- whatever you think about Keynes' analysis in that book -- his account was enormously persuasive at the time. And it was persuasive because it reflected what much of the diplomatic community already believed about the Treaty of Versailles, based on the prevailing economic wisdom of the prior quarter century. Indeed when Bernard Baruch, an adviser to American President Woodrow Wilson, penned the official American rejoinder to Keynes, he didn't really dispute Keynes' analysis of the treaty, but instead denied that a better treaty was possible and claimed that the faults of the treaty could not be pinned on Wilson or the Americans.

Much of Keynes' account still feels intuitive today. The war had been extremely expensive, it had caused extraordinary damage and it was unreasonable to think that everything would just naturally return to growth and glory if everyone paid their debts and moved on. But the new system Keynes concocted to save Europe was remarkably close to the laissez-faire orthodoxy of the time -- just do free trade again, with the caveat that the enormous debts created by the war must be eliminated so that countries actually have the money to spend on construction, investment and production. Instead of shipping gold off to foreign creditors, spend it rebuilding schools and factories.

At the end of World War I, then, Keynes aimed to preserve as much as possible from the old order that had fallen apart at the outbreak of war. His grand plan for the age to come was to clear out the debts and restart the system. Canceling the debts was a small price to pay, and indeed according to Keynes would ultimately result in a wealthier world, since real wealth was created not by financial flows but the movement of real resources to socially productive ends.

The depth of Keynes' faith in free trade, in other words, made him dismiss claims about moral hazard and the like that we often hear with regard to debt cancellation. It was free trade, not financial wizardry, that would save the world.

I mentioned Hayek earlier, and while I think Hayek often misread other thinkers, I do think it's useful for people to understand that despite their later differences, Hayek thought very highly of The Economic Consequences of the Peace. I take that as evidence that Hayek could at times be more flexible than the reputation he cultivated later in life might suggest, and also as evidence of the modest nature of Keynes' reform program at that time.

So much for World War I. By the end of World War II, however, Keynes had developed a completely new economic theory that rearranged his views about debts, trade, and everything else. When the only economic management tool you have is the tariff, free trade seems like a pretty essential policy. But one consequence of the Keynesian revolution was the legitimation of a bunch of other new tools that rendered the efficiency gains of free trade less impressive. If you could create massive economic growth by taking on government debt, then the edge in efficiency from trade might not seem like such a big deal. Indeed debt itself might not seem like such a big deal if a country was becoming more prosperous and productive by taking it on. And this was particularly true for a place like the British Empire, which could rely on politically friendly trading relations with much of the globe, even if it lost trading partners in other places by trying to protect key British industries.

After the experience of the Depression, Keynes downgraded the importance of free international trade and upgraded the value of legal stability. Keynes of course recognized the efficiency gains from comparative advantage -- but much of the real value of trade was not about efficiency as such, but rather about predictability. It is much better to have some set of generally agreed upon rules -- however bad they might be -- than the state of perpetual revision, failure, default and other varieties of economic anarchy that had prevailed in the 1920s and 1930s.

The postwar rules of the game were negotiated at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944. And although Keynes lost most of the battles he fought with the United States government at those talks, the prior intellectual triumph of The General Theory meant that the type of rules under discussion were vastly more flexible than those of the gold standard order that had prevailed at the turn of the century.

Countries were permitted to operate their monetary and fiscal policies in whatever manner they liked. They could even set up protective tariffs under some circumstances, and block the outflow of capital in emergencies. The IMF would stand ready to assist countries in need of temporary funds to deal with imbalances of trade, while the World Bank would invest in rebuilding, a vision ultimately replaced by U.S. investment from the Marshall Plan. In short, the Allies of World War II did not restart the old system, they built an entirely new economic paradigm around new postwar political realities, using new techniques of economic management.

So how, if at all, does any of that apply to today? If we want to understand our world through the eyes of John Maynard Keynes, the question to ask is whether the current historical moment is more like 1918 or 1944. Do we need a few technical reforms and a robust, renewed commitment to the economic program of the last generation, as Keynes advised in The Economic Consequences of the Peace? Or do we need to build a new global economic paradigm, as Keynes helped to do at Bretton Woods?

For much of the past year economists have been arguing about whether governments spent too much and ran the economy too hot during it efforts to keep consumers, creditors and businesses afloat in 2020 and 2021. At this point I think it's pretty clear that demand is running very high, at least in the United States -- but equally clear that we won't be rid of the inflation problem until the supply chains have been cleaned up. Excess demand may or may not be exacerbating inflation caused by production shortages, but production shortages are the root problem.

When Nicolette first reached out to me about this event, I thought my focus would be on reshoring and supply chain resiliency as a slow and arduous process for a dysfunctional U.S. political system to implement. But in the intervening weeks of course Vladimir Putin began his monstrous invasion of Ukraine. The sheer hostility of this act and Putin's open appeal to the imperial grandeur of the Czars to justify a murderous campaign against maternity wards and children's hospitals leaves the rest of the world with few morally compelling options. It is hard for me to imagine the economic sanctions against Russia being lifted, and even if some agreement is reached in which they formally come to an end, investors are not simply going to flock back to Russia overnight, nor can the nations of Europe and the United States plausibly remain dependent on Russian resources. In every conceivable endgame, Germany and Eastern Europe will eventually wean themselves off of Russian energy. After Putin's very public and explicit declaration of brutality, doing otherwise would be insane.

What all of this means is that scarcity in the global economy is about to become a much bigger problem even than it has been over the past year. In addition to energy, Russia extracts large amounts of the base metals and chemicals that go into everything from heavy manufacturing to agricultural fertilizer. Transitioning Western economies away from Russian resources can go a lot of different ways, but it will take time and involve real up-front costs.

Additional public debt in this environment can be good, if it is used to help pay to resolve these transitional costs. The world will need a lot more investment to replace the resources it is losing from Russia, and that investment won't just materialize from the gumption and derring-do of rugged entrepreneurs. Governments will have to incentivize and direct it.

Debt in this environment can also be bad, however, if it is used as a rationale for governments not to make the necessary investments in a prosperous and peaceful future. My own view is that the fundamental problems of the next few years are not about moral hazard or financial markets. What really matters is rerouting global trade and securing stronger supply chains that are resilient not only in the face of public health shocks like pandemics, but to the obvious political risks present in the world today. The general problems of the next few years are not going to be too much debt or too much demand. They will be the problems of too little supply and ineffective coordination among allies.

These are problems of course, but they are problems that can be solved. It is time for Western countries not only to coordinate their diplomacy against Russia, but to negotiate a new global trading order in which Europe and the United States are able to maintain material prosperity without relying on resources from strongmen bent on waging world wars.

The really hard questions in this process are not about debt as such. They're about what kind of international order is possible. The world is already rerouting its business away from Russia, but China is another story and a much bigger story for the global economy. It is clear today that Xi Jinping miscalculated his first major diplomatic maneuvers on the world stage -- and that he miscalculated every bit as disastrously as his ally Vladimir Putin did. Beijing's declaration of undying friendship with Moscow just a few weeks before Putin's invasion of Ukraine, its foreknowledge that Putin would be invading, and its request that Putin delay the attacks until the Beijing Olympics had concluded all show that Xi either disastrously misread his ally's intentions, underestimated the international reaction to Putin's aggression, or both. China has spent the weeks since the Russian assault trying to split the baby -- eager to maintain its trade links with Europe, while rhetorically denouncing the United States and parroting Russian propaganda blaming America for the debacle in Ukraine. These are not the actions of a responsible global steward, but China is also clearly uncomfortable with its current position and may yet change course.

But whatever happens, the time for leaders to plan for the next phase is now. The political climate in the United States has improved somewhat recently, but it is not good. When the last president of the United States tried to blackmail Volodymyr Zelensky as a favor to Vladimir Putin, his entire political party in Congress, with the exception of Mitt Romney, voted to support him. I do not think such openly pro-Putin behavior will be politically possible in the United States again anytime soon, but building a new economic order is hard, and it will only get harder if Biden is out of the picture in a couple of years.

My final point before I turn it over to Doug is that in economics and politics we tend to talk as if the progressive pursuit of egalitarian social goals is risky, while conservative programs that accept the status quo are safe and sound acts of prudence. That does not describe the options now before us. The question is instead a matter of what constitutes prudence. In my view, strict adherence to the economic norms of 1999 in today's world would not be prudent, but reckless. What we owe to future generations is not just an accounting ledger with the right balance of public debt and public assets, but a world where a decent life is available. It does the children of today no good to be free of debt if their parents are out of work and their cities are in flames.

This was how Keynes saw things when he read Hayek's Road to Serfdom as he steamed across the Atlantic to Bretton Woods. "In my opinion it is a grand book," Keynes wrote to Hayek. "We all have the greatest reason to be grateful to you for saying so well what needs so much to be said. You will not expect me to accept quite all the economic dicta in it. But morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it; and not only in agreement with it, but in a deeply moved agreement." His objection was not to Hayek's end, but to his means. "A change in our economic programmes" -- abandoning the New Deal and the Beveridge Plan -- "would only lead in practice to disillusion with the results of your philosophy." If Liberalism was to survive, it would have to adapt to the realities of the day. So it is in our time.