Left, Right and Keynes

Today's centrists are a hot mess.

My latest piece for The New York Times is up. It’s a look at the intraparty chaos over President Joe Biden’s economic agenda, and I encourage you to read it. The historical material involved is a lot of fun, so I’m going to expound on it here.

At the end of 1933, Keynes was worried that Roosevelt was about to blow the recovery by under-spending and trying to balance the budget. So he wrote the president a very long letter telling him to stop screwing around and spend some money, and he published it on New Year’s Eve in The New York Times. Authoritarianism was on the march across Europe, and Keynes saw in Roosevelt the world’s last hope for liberalism and rationalism. It’s a great letter — Keynes at his most arrogant and astute, lecturing the most powerful man in the world about about British politics, American politics and the silly economic fallacies that FDR’s economic advisers were committing, all while tossing off zinger after zinger (trying fix the depression with easy monetary policy alone is like “trying to get fat by buying a bigger belt”).

The Times keeps digital records of the physical pages from its back issues online, and this particular edition tells us a lot about Keynes’ status as an American celebrity, and also about the way Keynes developed his high theory from working with the problems of the day.

The Times currently has a Nobel Laureate on staff who writes wonderfully, but his material runs way back in the paper with the other opinions. In 1933, Keynes landed a 2600-word open letter on page 2! This is a level of fame that intellectuals simply no longer possess in American life — the stuff of royalty and movie stars. When he married Lydia Lopokova in 1925, Vogue magazine ran a feature on the wedding. Let your body move to the aggregate demand!

And note the substance of Keynes’ advice to FDR: spend money, run a deficit and jobs will come back. This is the policy program that most people today associate with The General Theory, but The General Theory didn’t yet exist. By the end of 1933, in fact, Keynes had been advocating that basic agenda for more than four years, but he wouldn’t have a full theoretical justification ready until 1936. Sometimes ideas shape events, and sometimes events shape ideas.

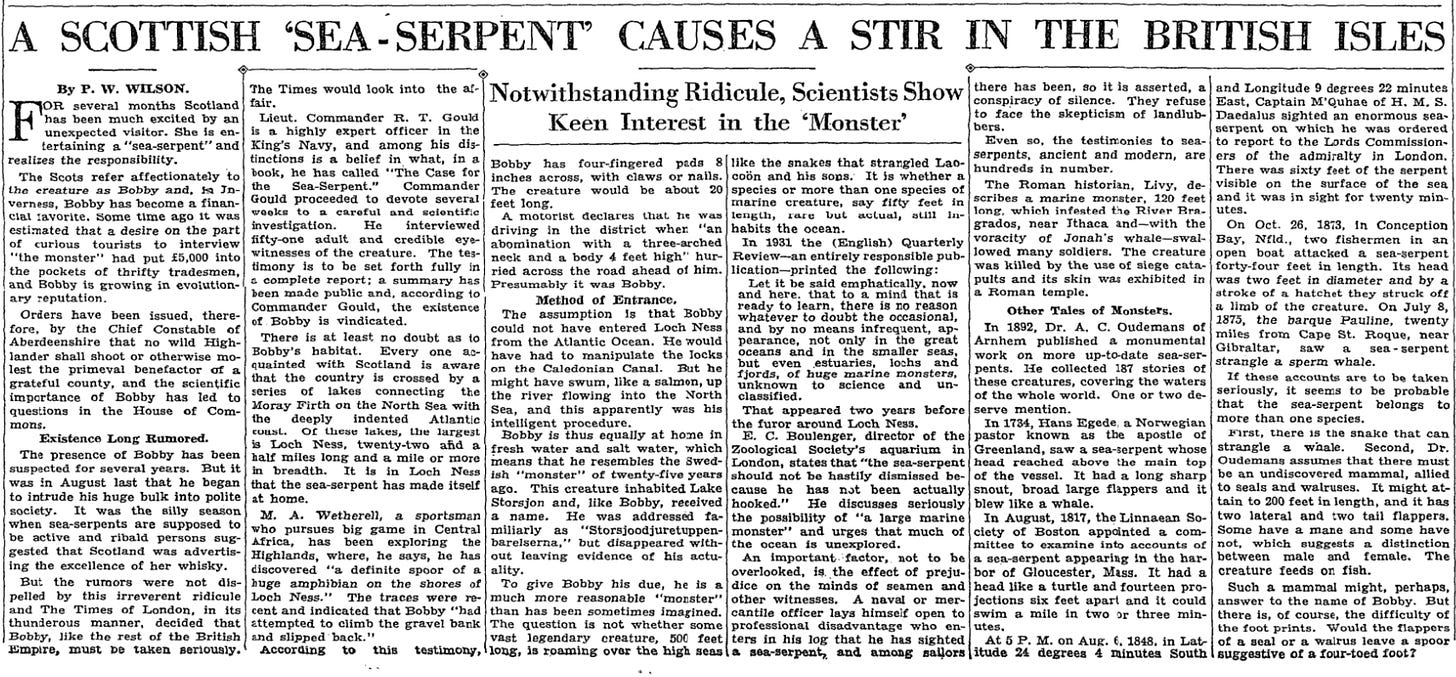

But even Keynes had limits to his fame. He was bumped from the front page to make room for this story about a ‘Sea Serpent’ from Scotland.

Today, Keynes and FDR are generally associated with progressive liberalism. This makes sense, because the policy agendas they pursued are very similar to the policy agendas pursued by today’s progressive liberals. Indeed in many respects they were more aggressive — the clarion call from the Bernie Sanders campaigns was for nationalizing health insurance. In the 1940s, Keynes helped nationalize all of British medicine.

But Keynes also had a deep conservative streak. He loved Edmund Burke and feared political revolution, thinking it generally bad for art and letters and all the fine things produced by high culture. And so there is an important sense in which Keynes was also a centrist. He fought off calls for radical political change from the left and the right with an appeal to economic reform.

Critically, this centrism had an active policy agenda. It was committed to new ideas and their implementation — it aimed to actually achieve something through positive action. It did not merely seek to pare down the ambitions of other factions, it had ambitions of its own. This is what the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. called “the vital center” in a 1949 book of the same name. It was not his most popular book, but about half a century later, one of its fans named Bill Clinton started appealing to “the vital center” in speeches celebrating the neoliberal turn of the Democratic Party. This incensed Schlesinger, an ardent New Dealer, who wrote an op-ed slamming Clinton for abusing his phrase. Clintonism was not “the vital center,” he argued, it was “the dead center.”

The situation with today’s centrists in the Democratic Party is similar, only much worse. Joe Biden is a lifelong centrist who is fighting back progressive calls for structural political change with a commitment to robust economic reform. Adding new states to the union, adding new seats to the Supreme Court, eliminating the electoral college, abolishing the filibuster — Biden has politely ignored them all. But people calling themselves centrists are now attacking Biden’s economic reforms — the very centrist agenda that is supposed to help beat back the demands from the left and right.

Not a single one of Biden’s intraparty critics has offered a coherent policy justification for their opposition. They’ve abandoned centrism as a set of ideas with a clear purpose and embraced an amorphous fear of action itself.