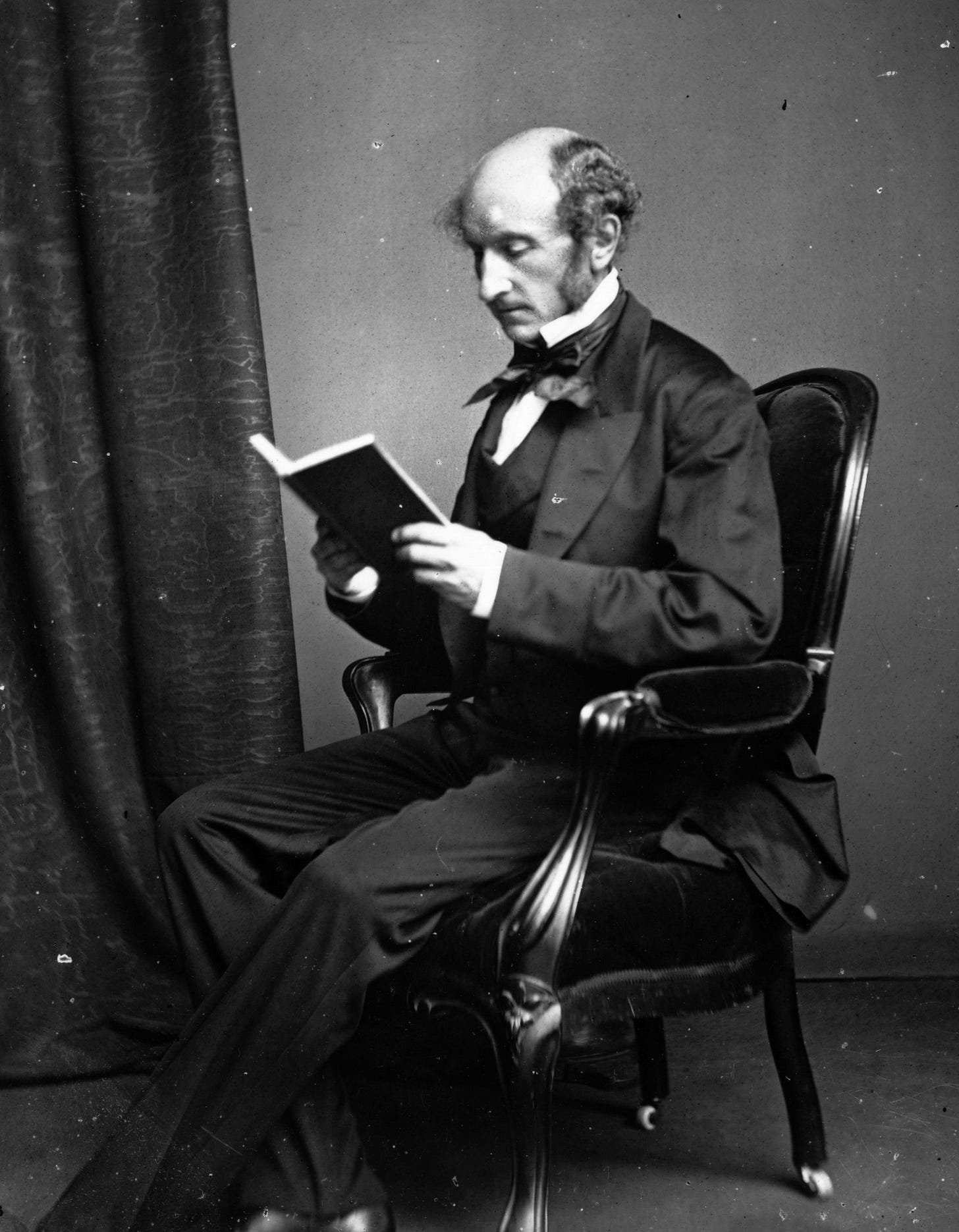

My next book will be a biography of John Stuart Mill. So far, I’m enjoying it very much. Mill was an unusual man who lived an extraordinary life devoted to a set of problems that once again dominate political thought in the 21st century.

I try to be cautious about describing a long-term project like a book early on, because whatever you think you're writing at the outset is inevitably transformed by what you learn along the way. When I pitched my proposal for The Price of Peace, I wasn't planning to spend a whole lot of time on Keynes in the interwar years. But of course that plan was ridiculous and I abandoned it as soon as I encountered a letter Keynes wrote in 1923 about getting lost in the countryside on a fox hunt gone haywire. I don't expect much on foxhunting for the Mill book — it will be about the things I find most interesting, namely liberalism, democracy, war, and sex — but beyond that, it’s still hard to say.

Last month, however, the New York Times published an extraordinary series on the economic and political history of Haiti (including a 5,400-word piece detailing the paper’s research methods and sources). And this week, I came across some writing from Mill on Haiti that I think helps illuminate the way early 19th century thinkers understood some of the events in the Times series. It’s too interesting to keep to myself until the book comes out, so I’ll share it here.

In 1824, a new publication called the Westminster Review enlisted Mill to write an essay blasting the hell out of a rival publication called the Edinburgh Review. In the essay, Mill essentially called the Edinburgh editors a bunch of rich sellouts who were too selfish to think straight. His most damning piece of evidence was an Edinburgh article that had defended France’s claims on Haiti. The Edinburgh, Mill noted with palpable disgust, had implored the people of Britain to support France against the Haitian Revolution, on the grounds that a new, self-governing Black nation would be dangerous to nearby British colonies. Mill really let the Edinburgh have it, but what I find most interesting about his attack is his evident disinterest in making a detailed argument. The persuasive force of his rhetoric comes from simply restating the Edinburgh's position and declaring (correctly) that it is morally horrendous. The great Edinburgh Review, Mill jeered, had been ready to condemn an entire nation "to the alternative of death, or of the most horrible slavery" in order to protect the profits of a few plantation owners.

This tells us at least four important things about the intellectual climate of the early 19th century. First, there were people who regarded what France was doing to Haiti as a great crime, and said so. Second, for a substantial population, merely reciting what France had done to Haiti was enough to generate moral outrage. You didn't have to explain to this crowd that it was wrong to enslave human beings, or that it was wrong to fight wars in defense of slavery. They knew.

Third, there was a very detailed spectrum of opinion in 19th century Europe on human rights. Even Mill’s targets at the Edinburgh explicitly acknowledged “the unmerited sufferings of the unhappy negroes” in Haiti — they simply denied that righting those wrongs trumped the commercial interests of British colonists. In the United States, we’re accustomed to thinking about the slavery question as a pro-con dichotomy, a habit encouraged by a very bloody Civil War that was fought to end “the peculiar institution.” But there were many different ways to “oppose” slavery. There were reformers who wanted to pay off enslavers, reformers who wanted to imprison enslavers, and reformers who only had a problem with slavery when it was carried out by other empires. Functionally, this meant that a great many people could applaud themselves as broad-minded humanitarians, while also esteeming political “moderation” that bent public policy to the benefit of those who profited from slavery.

Fourth, and perhaps most important, Mill’s missive helps demonstrate the political limits of intellectual discourse in the early Liberal era. Some of the most famous minds in Europe decried the plundering of Haiti, and it was plundered anyway, and then plundered again, and again. Not because nobody knew any better, or because plundering was inevitable, but because people with power really wanted to do it.

There’s much more that could be said, of course, but that’s what the book is for. I’ll leave you with Mill:

The other article to which we alluded presents a remarkable contrast with the tone which the Edinburgh Review afterwards assumed, on the subject of negro slavery. Its object is, to prove that we ought to wish success to an armament which the French government was then fitting out against Hayti; and that we ought even, if necessary, to assist the French in their enterprise. When we consider what that enterprise was -- an enterprise for the purpose of reducing a whole nation of negroes to the alternative of death, or of the most horrible slavery; and when we consider upon what ground we are directed to co-operate in it, namely, the danger to which our colonies would be exposed, by the existence of an independent negro commonwealth, we can have no difficulty in appreciating such language as the following:

We have the greatest sympathy for the unmerited sufferings of the unhappy negroes; we detest the odious traffic which has poured their myriads into the Antilles; but we must be permitted some tenderness for our European brethren, although they are white and civilized, and to deprecate that inconsistent spirit of canting philanthropy which, in Europe, is only excited by the wrongs or miseries of the poor and the profligate, and, on the other side of the Atlantic, is never warmed but towards the savage, the mulatto, and the slave.

To couple together "the poor" and "the profligate," as if they were two names for the same thing, is a piece of complaisance to aristocratic morality which requires no comment. Then all who venture to doubt whether it is perfectly just and human to aid in reducing one half of the people of Hayti to slavery and exterminating the other half, are accused of sympathizing exclusively with the blacks. We wonder what the writer would call sympathizing exclusively with the whites. We should have thought that the lives and liberties of a whole nation, were an ample sacrifice, for the sake of a slight, or rather, as the event has proven, an imaginary addition to the security of the property of a few West-India planters. This is, indeed, to abjure "canting philanthropy." What it is that the reviewer gives us in the place of it we leave the reader to judge.

Congrats! Is an announcement on some of the special projects involving paying subscribers imminent? As someone who greatly enjoyed the Price of Peace and has an interest in writing an econ/politics-centric book someday down the road, I’d love to learn more about your process as you work on this book.