An Old-Fashioned Crisis for American Democracy

The Roe repeal demonstrates once again that American conservatism is not a doctrine of caution or humility.

The most frightening implications of the Supreme Court's apparent plan to overturn Roe v. Wade do not involve abortion.

Justice Samuel Alito's brazen, bizarre draft opinion would undoubtedly engender tremendous, unnecessary suffering for countless Americans. Even in the most restrictive red states, thousands of women receive abortions every year, both in clinics and by prescription. What it means to be a woman in red America -- and what it means to have women in your family -- is about to change dramatically, for the worse.

But embedded in Alito's inflammatory language is an extraordinarily radical conception of American government, grounded in a worldview held by only about a fifth of the U.S. population, invoked to detonate a Constitutional right that has been accepted under American law for half a century. As a result, repealing Roe entails not only a disaster for women's rights or even the legitimacy of the High Court — but a crisis for American democracy.

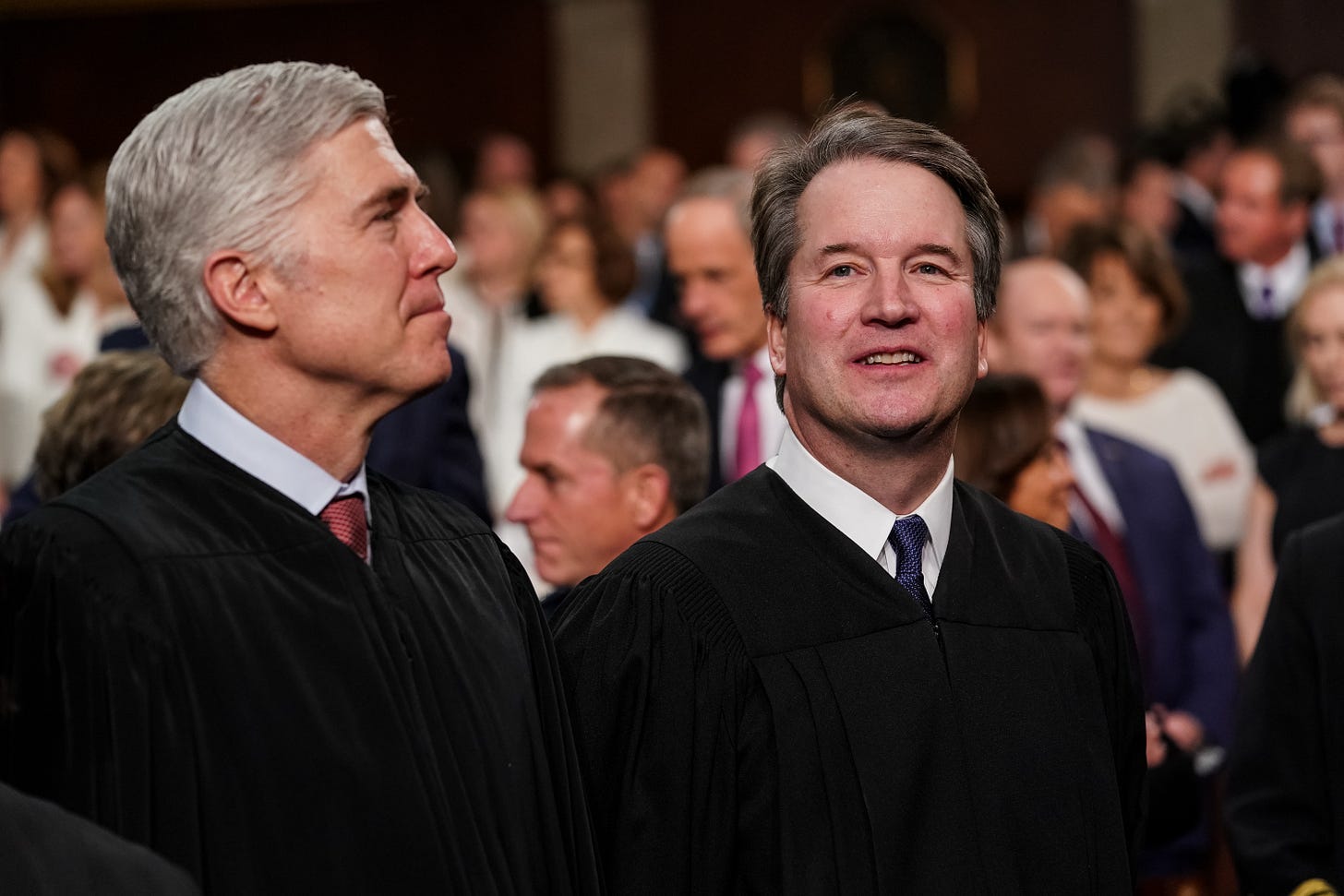

And so I find myself agreeing with New York Times columnist Bret Stephens. To the best of my knowledge, this has never happened before. In an open letter to the Court's conservative wing, Stephens emphasizes that whatever one thinks about the merits of Roe, overturning it would require a sweeping transformation of American life that most people associate with radical social change, not cautious conservatism. Exchanging a settled legal consensus decades in the making for the views of a fringe, fervent minority is, Stephens argues, an invitation to social upheaval. And the testimony of sitting conservative justices in recent confirmation hearings will only make matters worse. Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh both emphasized the degree to which Roe had been settled law, confirmed as legal precedent. To put it more bluntly than Stephens does, the draft opinion makes them look like lying cranks. No democracy will accept such an outrage lying down. No one can predict exactly how the ensuing culture war will be resolved, but the fabric of the nation will be tested.

Rebecca Traister and others have detailed the extremism of Alito's draft opinion language. He uses derisive terms ripped from the talking points of far-right activists, calling those who support abortion rights "abortionists" as he invokes both the Dred Scott decision and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II as judicial debacles comparable to Roe. Nobody deploys such language by accident. Alito and his allies are deliberately insulting a significant majority of the country, along with the memories of the three Nixon appointees and two Eisenhower appointees who issued Roe and the two Reagan appointees, the Ford appointee and the George H.W. Bush appointee who upheld Roe in Casey vs. Planned Parenthood.

The Court almost certainly recognizes all of this at some level. Though it remains unclear who leaked the draft opinion and why, the Court surrounded itself with barricades shortly after Politico broke the story, anticipating immediate public uproar. They are perfectly aware that the country is furious.

But while Stephens is undoubtedly correct to emphasize the recklessness of Alito's draft opinion, he is obviously wrong to describe the court’s Roe crusade as a departure from conservative business as usual. The conservative movement has been trying to engineer this moment for decades. Abortion has dominated every aspect of the court appointment process throughout my lifetime, while public polling on abortion has never substantively changed. The vast majority of Americans believe Roe should be upheld. About 20 percent of the country wants abortion banned outright, opposite about 30 percent who support legal abortion at any time for any reason, while the remaining half of the country wants abortion legal under some but not all circumstances.

The conservative movement has always known it is trying to impose the views of a small minority on the country at large, through the least democratic mechanism in American law. And everyone who follows the court knows that a willingness to repeal Roe is a litmus test for Republican SCOTUS nominees. It is a bit rich to see Stephens — who has long written admiringly of Trump appointees Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh — admonish those same Justices for doing exactly what they were hired to do.

Nor is conservative support for radical change limited to abortion. The zeal for bank deregulation in the 1990s eliminated safeguards that had been in place since the 1930s, in service of a new, untested financial architecture. Paul Ryan's attempts to eliminate Medicare and Social Security took aim at social insurance programs that have served Americans longer than he has been alive. The economic globalization project that conservatives pursued in the 1980s and 1990s was a new way of organizing international resources and production. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan sought to overthrow existing governments in favor of newer, better political systems crafted by American foreigners. For decades, the American right has evinced a perpetual thirst for rapid social change, so much so that Milton Friedman believed his political allies had misnamed themselves. When asked in 1978 if he identified as a "conservative," Friedman responded: "Good God, don’t call me that. The conservatives are the New Dealers like [John Kenneth] Galbraith who want to keep things the way they are. They want to conserve the programs of the New Deal." Even the hip, fresh stuff on the American right is, well, new. Abandoning the public dollar for private cryptocurrencies would be a pretty dramatic overhaul of the global financial system.

This is not merely a semantic squabble over the meaning of the word "conservative." The people who control the Republican Party and conservative political infrastructure in the United States are not afraid of change, and never have been. They do not view themselves as bound by legal precedent, national tradition, or cultural consensus. They perceive themselves as an increasingly embattled minority seeking to impose its will on a hostile majority. And after decades of painstaking work, they control the Supreme Court, which simply cannot function as a nationally credible arbiter of social disputes so long as they do. The court has been losing legitimacy since Bush v. Gore handed the presidency to George W. Bush by refusing to count votes. After the Roe repeal, it will rightly be regarded by ordinary Americans as the operating headquarters of a fringe political faction.

Against the program of these five justices, it is tempting to applaud the more moderate path taken by Chief Justice John Roberts, who is famously protective of the Court's perceived legitimacy. But while Roberts' approach does show much more caution than that of the court's radical right, it is no less anti-democratic. Roberts has long believed that a primary flaw in American politics is an excess of voting rights. And so he has been working steadily to restrict the franchise since the 1980s. Roberts does not want the Supreme Court to impose right-wing priorities, he wants elected officials to do so, acting on behalf of a narrow, enlightened electorate.

This, too, is a program of sweeping political change that has already functionally eliminated long-cherished constitutional rights for many, and will almost certainly eliminate more before Roberts is through. Instead of issuing controversial Court rulings on hot-button social issues, Roberts will continue to tip elections to the right through legalized voter suppression. In Alito's version of conservatism, minority rule serves as a means. In Roberts' version, it's the end.

I will not venture a comprehensive definition of conservatism here, but I think it is important to recognize that the project we call conservatism in American politics is much more concerned with the erosion and restriction of democracy than with social stability, tradition, or any other way of venerating the historical past. This brand of thought controls the Supreme Court and animates the Republican Party, irrespective of whether Donald Trump is running the show (which, it appears, he is). And that means that the dominant battle in American politics is American politics -- the unsettled question of whether we will continue to function as a democracy.

Great read as always. Slightest disagreement with the crypto stuff though, Keynes argued for a bancor and didn’t get his wish because of politics. Now we have the technology to create our own bancor and have done so, in part because we realize we cannot trust those in power. They bail out the rich repeatedly at the cost of the middle class; bitcoin is one of few defenses we have against them.

Sad time for democracy. I hope the pushback from democrats against the court is swift and strong; either pass the laws or pack the courts. We cannot allow a meek response.